From Gladiators to Google Ads

Marketing and content creation might seem like modern inventions, but humans have been in the storytelling and persuasion business for millennia. In fact, if you wandered into an ancient Roman city, you’d recognise surprisingly familiar tactics: eye-catching ads on walls, sponsored events, and even celebrity endorsements (gladiator influencers, anyone?). From the graffiti of Pompeii to today’s viral videos, the methods have evolved with technology, yet the core principle remains the same. It’s all about grabbing attention, telling a story, and getting people to buy in.

When in Rome: Graffiti, Gladiators, and Guerilla Marketing

Ancient Rome didn’t have Piccadilly Circus or social media, but it certainly had advertising and PR. It’s walls were the Facebook of antiquity, plastered with messages that ranged from love notes and insults to political slogans and event promos. You could find painted inscriptions announcing upcoming gladiatorial games, proclaiming support for political candidates, or even the equivalent of giant lost-and-found flyers for missing livestock. The locals treated walls like communal notice boards, proving that our urge to “post” and share is nothing new.

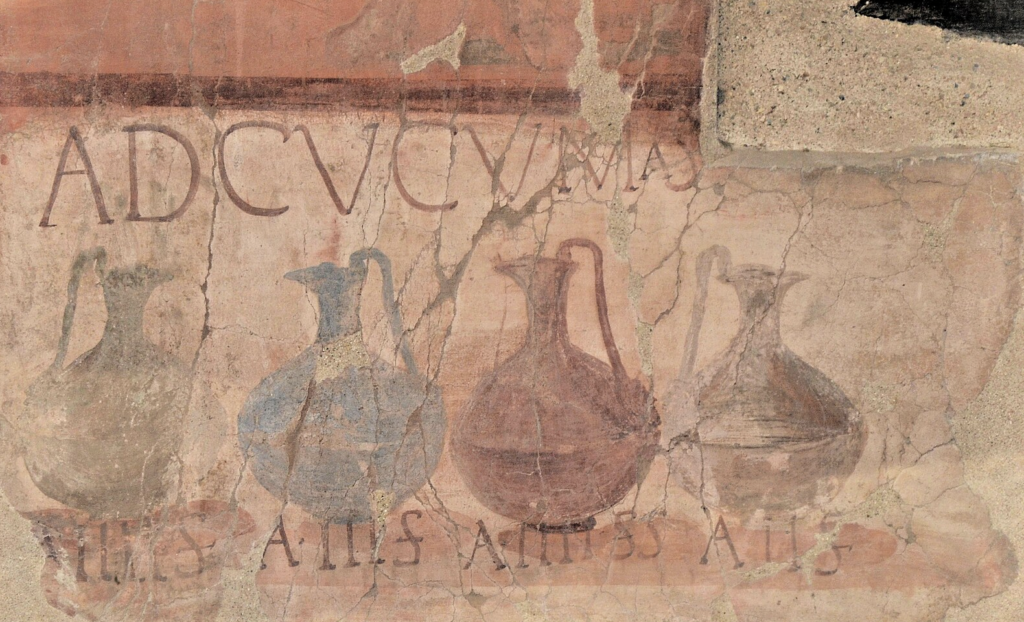

But Roman marketing went beyond graffiti quips. Walk down a Roman street and you’d see shops and taverns with visual signage and branding meant to lure customers. Many businesses hung painted plaques or mosaics above their doors, a bit like logos. For example, one Herculaneum wine shop’s sign (beautifully preserved by Vesuvius’ ash) was a painted advertisement listing different wines and their prices, under the bold heading “Ad Cucumas” (Latin for “At the Jugs”). Step into another alley, and you might encounter a more provocative logo: an actual stone relief of four phalluses and a pair of dice cups, marking the entrance of a small gambling hall in Pompeii. Crude? Perhaps, but it got the message across. (In Rome, luck and…let’s say virility…were intertwined symbols, so this was basically the ancient equivalent of a neon sign saying “Good Fortune Inside: Open 24/7!”).

Even Roman products had branding that modern marketers would appreciate. Amphorae (clay jars) of olive oil or the beloved (and rather pungent) fish sauce garum often bore stamped names or insignia of their producers, building their reputation across the empire. Aulus Umbricius Scaurus, a wealthy Pompeian garum tycoon, famously decorated the floor of his house with a mosaic of a garum jar labeled “from the workshop of Scaurus”, essentially a permanent ad for his own best-selling sauce. He clearly understood the value of product placement; why hang a poster when you can tile your brand into your foyer?

Of course, the biggest spectacles in Rome, gladiatorial games and chariot races, doubled as massive marketing opportunities. In the lead-up to a gladiator match, sponsors commissioned hand-painted notices on walls all over town. These ads hyped the event with details any sports fan would love: who the star fighters were, their record of wins, and juicy promises like venatio (wild beast hunts), or the provision of awnings to shade the spectators. Crucially, the posters always named the sponsor footing the bill. (After all, if a local bigwig is spending a fortune to entertain the masses, he wants everyone to know it’s his show). Essentially, the ancient form of corporate sponsorship. On the days of the games, promotion continued inside the arena. Politicians and patrons won goodwill through giveaways that any modern event marketer would admire; tossing free bread and coins into the crowds or hosting lavish public feasts as part of the festivities. “Bread and circuses” wasn’t just a policy; it was savvy PR. By splurging on crowd-pleasers, sponsors essentially said, “Remember me next election, and enjoy this on the house!” It worked about as well as today’s event sponsorships (if not better, considering emperors literally became beloved for funding games).

Interestingly, ancient Rome also had hints of influencer marketing. Gladiators were the superstar athletes of their day, people cheered their names, hailed them as sex-symbols, scribbled graffiti about them, even bought merchandise like oil flasks with gladiators’ likeness. It’s said that some popular gladiators endorsed products like ointments or wines outside of the arena.

In short, the Romans mastered the art of content and communication long before “marketing” was a job title. They leveraged visuals, catchy messages, social status and public forums (literally, forums) to promote everything from taverns and sauces to political careers. In essence, the Romans knew, much like the marketers of today, that to win hearts and minds (and coins), you need a good story, a bold message and maybe some free merchandise to throw to the crowds.

Signs of the Times: Medieval Markets and Manuscripts

When Rome fell, its communication framework crumbled too. Yet the instinct to promote didn’t vanish. In medieval Europe, with most people illiterate, marketing relied heavily on symbol and sound. Picture a medieval market: narrow lanes packed with stalls, the air thick with smoke, music, shouting. Traders needed signs that spoke without words. A boot swinging above a cobbler’s door. A striped pole twirling outside a barber-surgeon’s. Three golden balls for a pawnbroker. These weren’t just shop signs, they were addresses and advertisements rolled into one.

By the late 14th century, English law required inns and taverns to display signs or risk fines (or worse, the loss of their ale licence, a grim fate). This bureaucratic nudge led to a boom in painted placards and eccentric pub names: The King’s Head, The Drunken Duck, The Prancing Pony (Tolkien fans will know this one). The signs were often hand-crafted and eye-catching, designed to beckon travellers or thirsty locals. A well-made sign was the backbone of a successful medieval business.

Not just signage, but town criers roamed the streets, bell in hand, bellowing news, royal decrees and paid announcements. They might declare the arrival of a merchant ship, an upcoming fair, or the reward for a runaway swan (Hot Fuzz style). These walking broadcasts were impossible to ignore, and they knew how to hold a crowd. Think of them as early push notifications, except with more shouting.

Meanwhile, in scriptoria and university towns, a subtler form of marketing emerged. Monks and scribes, who painstakingly copied manuscripts, sometimes left personal notes at the end: part piety, part promotion. A typical colophon might say something like, “If you liked this book, I can make you one too.” Not so far from “please like and subscribe.”

Stationers in cities like Paris or London displayed decorative pages in their windows to show off their illumination skills. A dazzling initial or border was their equivalent of a demo reel, not just decoration, but bait for commissions. And so, even in an age without mass printing, word of mouth, visual craft, and human voice kept the flame of marketing alive.

Then came Gutenberg, and with him, a revolution.

Paper Empires: Print, Posters, and the Birth of Mass Marketing

The printing press transformed everything. Suddenly, messages could be replicated at scale and speed. Almost immediately, people began using it for promotion. England’s first known printed advert, a small flyer by William Caxton in 1477, promoted a handbook of church rules. He highlighted its affordability, accuracy, handsome typeface and where to buy it. It was the 15th-century equivalent of a product listing.

By the 1600s, pamphlets and broadsides were pinned to walls and thrust into hands across Europe. Markets, fairs, sermons and miracle cures, all publicised via cheap print. Newspapers arrived soon after, bringing a regular slot for notices, announcements and classified ads; the beginnings of commercial media.

Then came Josiah Wedgwood. The 18th-century pottery genius understood marketing in a way that still feels modern. After gifting an elaborate tea set to Queen Charlotte, he launched a commercial line named “Queen’s Ware”, fine china for the rising middle class, marketed with royal clout. He opened showrooms, published catalogues and used testimonials. He even published pamphlets about his glazing techniques to lend his brand a veneer of science. Wedgwood wasn’t just selling plates. He was selling aspiration; something mirrored consistently today through luxury brands like Ferrari, Rolex or Hermès. They’re not selling products, but lifestyles.

As the 19th century progressed, marketing became more sophisticated. Copywriting emerged. Visual identity became standard. Newspapers carried ads for everything from soap to spectacles, often dressed with slogans and celebrity endorsements. Even Charles Dickens dabbled in endorsements. By the end of the century, advertising wasn’t a sideline, it was a profession.

This was also the birth of what we now call content marketing. In 1895, John Deere launched The Furrow, a magazine offering farming tips (and occasional nudges toward Deere equipment). In 1900, the Michelin Guide debuted, offering travel tips, maps and restaurant reviews, all designed to encourage more driving, more miles, more tyres. Both succeeded by providing genuine value first, selling second. A model still very much in play.

Lights, Print, Action: The 20th Century and the Age of Broadcast

Electricity changed the game. First came illuminated shopfronts, then glowing signs that turned entire streets into rolling billboards. London’s West End and Paris’ Grands Boulevards lit up with a shimmering commercial vocabulary. When neon arrived, it sealed the deal. Advertising wasn’t just visible, it became luminous.

Then radio brought marketing into people’s homes. The first radio adverts were direct, sometimes clumsy, but undeniably effective. Within a decade, brands were sponsoring whole programmes. Some even created them. Soap companies underwrote radio dramas aimed at housewives, emotional serials that came to be known, rather fittingly, as “soap operas.” The formula was simple: hook the audience with narrative, weave the brand in naturally, and let familiarity do the work.

Television took this further. When the UK’s first TV advert aired in 1955 (for toothpaste), it marked the beginning of an era where advertising was no longer confined to margins. Brands now had moving images, sound and story at their disposal. By the 1970s, TV ads weren’t just persuasive, they were cultural artefacts. Some were funny, others heartfelt, others surreal. But the best all did the same thing: they made you remember.

Public relations emerged as a parallel force. Not just stunts and spin, but the crafting of stories designed to earn coverage rather than pay for it. In this sense, PR was as old as empire. Trajan’s Column, after all, was a 100-foot-tall press release carved in marble. Now, the techniques had been updated: media briefings, launches, carefully seeded narratives. A well-timed photo or quote could travel far.

By the end of the century, marketing had become a fixture in everyday life. You saw it on your telly, heard it on the radio, passed it on your commute, read it in the paper. The messages were slicker, but the motives hadn’t shifted. Reach people. Move them. Get them to care, and make sure they remember.

Digital Storytelling: Web, Social, and the Return to Roman Principles

Then came the web. The first banner ad in 1994 was simple, a question in a grey rectangle: “Have you ever clicked your mouse right here?” It looked basic, but it opened the floodgates. Online advertising exploded. Email campaigns followed, then pop-ups, then targeting. Soon, marketers could reach specific individuals at specific times with tailored messages. A Medieval town crier would have wept with envy.

But quantity became noise. Audiences tuned out. Brands had to pivot. Instead of shouting, they started storytelling again. The tools were digital, but the instincts were ancient. Blogs, how-to guides, brand documentaries, subtle product placements, all aimed at being entertaining or worth sharing. The modern marketer began to look more like an editor or a producer.

Then came the reemergence of influencers, now with ring lights and hashtags, but the principle still remained; people trust people. Gladiators once sold ointment. Now, a TikTok chef might shift knife sets. The format changes. The psychology does not.

Visuals returned with force. Infographics, reels, animations, shorts. Fast, sharp and easy to consume. Yet behind the flash was the same logic that powered Roman signage or Medieval shop symbols: show, don’t tell.

The best modern campaigns don’t just promote. They invite. They entertain or explain. They reward the viewer’s attention. In a world that scrolls at speed, earning a pause is half the battle.

The Eternal Power of Storytelling

From Pompeii’s painted walls to the glow of a phone screen at midnight, the platform might shift, but the purpose doesn’t. Humans respond to stories. We recognise emotion, a well-timed joke, a striking image, a moment of shared feeling; these are the real hooks.

The technology is dazzling, no question. We have augmented reality, AI, 3D avatars, data sets that would baffle Caesar’s census-takers. But strip it back, and the essentials remain the same.

That’s why this history isn’t just interesting, it’s instructive. For content creators, brand builders, strategists and storytellers, the path forward looks an awful lot like the path behind. Marketing has always been about understanding people and finding the right form to reach them; the good ones make the form disappear and let the message shine.

At Nicely Done Productions, we live in that tradition. We craft stories that cut through, because we know the oldest truth in communications: the best message is one people want to hear. Whether it’s animated, filmed or written in fire across the sky, what matters is the connection. The Roman merchant, the medieval town crier and the 21st-century creative director are all playing the same game.

So the next time you’re building a campaign or making content, remember: you’re not just competing with your contemporaries. You’re standing in a long, dusty queue of humans shouting for attention. The ones who last aren’t always the loudest, they’re the ones who know how to tell a good story.

By Aaron McNally